The Merapi volcano on central Java is erupting, killing dozens of people. One of the victims is mbah Marijan, the 'spiritual gatekeeper' of the active volcano. I interviewed him in 2001. In honor of this special man, here the interview from my Chavannes.nl archive.

Gunung Merapi, Central Java. (C)havannes

by Ole Chavannes, 27 oktober 2010

The gatekeeper of the Merapi

Published on chavannes.nl in April 2001

The Merapi volcano in Indonesia is the most dangerous in the world: an estimated 4 million Javanese live around the active ‘red fire’ mountain. With an imminent eruption, they only listen to mbah (grandpa) Marijan, an old farmer who is believed to have a supernatural connection with the spirits of the mountain. He is the gatekeeper.

Babad Tanah Jawi

"The noise sounded like a terrible thunder, rain of fire gushed down the mountain. Lava rivers flowed in all directions, burning many farmer villages directly. The population of the Mataram kingdom was terrified of the lava flows and ash rain. So he gave the king the command to pray to God, and the volcano stopped spitting fire." -quotation from the royal Babad Tanah Jawi writings, August 4, 1672.

It is the first written source that mentions an eruption of the Merapi in central Java. The Dutch East Indies government in Batavia (now Jakarta) received a week later the news that more than 3000 people were killed by the eruption. The kingdom of Mataram (now Yogyakarta) was for over 24 hours covered in darkness and almost entirely destroyed by the ongoing rain of ash and rocks.

Hot feet

The three kilometer high Merapi (merah = red, api = fire) spits large black clouds of ash and boiling lava every couple of years. The seismological station, halfway up the mountain, advises most of the time not to climb the mountain. Only a handful of farmers decline to respond. The mountain shows permanently steaming plumes of thick smoke and daily lava flows down.

In February 1996 I climbed the summit of Mount Merapi itself. Then only some yellow sulfur fumes came from the crater. It was a wonderful experience with sunrise on the rim of the crater, with hot feet by the earth and frozen fingers by the air. Only after we came down and paid our guide, he admitted we were actually not allowed to climb it.

There is only one man who always stays on the mountain, a friendly old farmer: mbah Marijan (74). He has lived there all his life, but was officially appointed by the Sultan of Yogyakarta in 1983 as the ‘gatekeeper of the volcano’. The position of the sultan is similar with royalty in Europe, in terms of hereditary succession, but he is also governor of the province and enjoys huge (holy) admiration. His political influence of his Kraton (palace) is great. The policy of the Sultan is a curious mix of rational considerations and traditional Javanese beliefs. Therefore, in Java, the most logical thing in the world, is not to recognize data from a seismological institute, but to appoint a clairvoyant farmer who claims to be able to interpret the ‘mind of the volcano’. Marijan only makes the decision to evacuation in case of eruption, or not.

Just an idiot

With a motorbike we slowly climb the steep hill. The rain is poring down and the muddy path is slippery. We go visit mbah Marijan, who lives in the village Kinahrejo, closest to the crater, located at 1300 meters altitude. The residents grow rice and vegetables in the highly fertile ash soil. Kinahrejo has never been evacuated, because it is a sacred village, according to the villagers. It is night, when we hear suddenly, hidden in the dense jungle, sounds from a building. It is the characteristic gamelan music. I knock on the door that swings open. Mbah Marijan is behind the biggest gamelan, together with twenty other villagers, practicing for a processional ride to the crater, later this month.

“Welcome, welcome, come inside”, he begins with a smile. If he can answer some questions about the volcano? “Sure, but I do not know if I can answer. I'm just a simple man, just an idiot”. He laughs at a crazy high tone.

Spiritual barrier

He starts telling: "Compared to last month's the Merapi is quiet now. Kinahrejo and by extension, Yogyakarta are safe, because it is protected by the stone elephants. It is a sacred stone in the form of a reclining elephant with a young lactating. Long ago, the stone stopped the lava that was about to hit a pregnant woman who just walked by. Since then, the sacred stone will stop any lava to flow through the village. It's like a spiritual barrier. I will show it to you tomorrow morning”. After several glasses of extremely sweet tea, the farmers decide to go home.

We may come with mbah Marijan to his home located a bit further. He lights up a heavy kretek (clove cigarette) and continues. “Next to the stone elephant there is an elephant tree. It is a sacred Bayan tree (a tropical species that usually doesn’t grow this high). The story goes that centuries ago, the last elephant of Java was killed under this tree by a great hunter, who was living there. I do not know if it is true. I once myself was meditating all night under the tree. When I looked up I suddenly saw a bright blue light coming from the Merapi. It fell straight on the tree and then it was gone”.

Mbah Marijan has probably told this story often to curious tourists. He is still unlikely

friendly, but he is tired too. We agree to meet again, the next morning. “See you at half past 5, that is when farmers get up”.

At night we hear the dark thunder from the volcano, less than six kilometers away. I start realizing this volcano is just one of many pulsating pimples with liquid stone on the thin skin of mother earth. I sleep bad.

Not black magic

Early in the morning we meet the gatekeeper at his stable, where he milks his only cow. “Shall we look at the tree and the stone?”, he smiles happy as always. Despite his advanced age and smoking addiction, he jumps up a slippery mud path. Along the way I ask him about his special skills to predict when the volcano begins to pop. “I'm not a black magic man”, he says, suddenly less friendly.

It is generally accepted in Indonesia that the political situation in the country is often measured by the activity of the Merapi volcano. When dictator Suharto resigned in 1998, the volcano also grunted a few times. How would he explain this connection? “Perhaps it is true that the heat of the earth makes people also feel hotter, so they are tempered and provoking. But people make politics, not the volcano”.

Kraton of ghosts

We arrive at the remarkable tree, surrounded by a wall with pink graffiti. The tree has

five branches, symbolizing the location and directions. I try to sense something ‘spiritual’, but all I feel is the hot and humid air.

Could you explain spirituality to this rational Westerner? He laughs. “I don’t care what others believe. I believe in the dream, but it's hard to explain. When my father died, I dreamed about him that night. Also villagers are sometimes visited in their sleep by Nyai Gadungmelati (a female ghost in a green robe, who dwells in the crater). It warns us of danger. We believe that just as the kraton in Yogyakarta, there is a kraton of the ghosts in the volcano. There are good and bad spirits and we, inhabitants of the mountain, better ensure that we respect them enough. We bring gifts during processions, to honor them. The mountain is rich and gives us everything. Without respect it will go wrong”.

Gas clouds

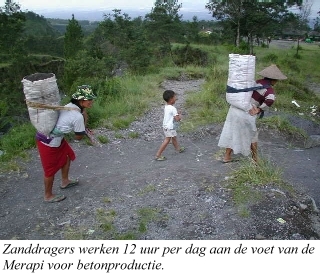

Mbah Marijan has to go, he has cut fresh grass for his cow. We walk further along the mountain and stand suddenly in a valley with hundreds of workers. They dig volcanic ash for the concrete factory. The ash sets off in a river of lava. Every time it rains on top of the volcano, a new layer of ash flows into the riverbed. The black sand is well suited for constructing buildings. Thin but strong men carry bags with 50 kilos of sand up and down tiny muddy roads, to dump the sand into trucks. One days works is good for 3 euros. Most of the workers present, are children.

We look over the deep valley under the mighty Merapi. A subtle sign next to the road says ‘warning: occasionally invisible gas clouds of 700 degrees Celsius flow down the hill within one minute’. We ask a girl, about 15 years old, if it is not too dangerous to work here. She pulls up her shoulders, laughing: “Nothing I can do about that. Ash clouds we can see coming, but there is nothing one can do against the gas. If that happens, you’re just gone”.

Always risks

Back at the house of mbah Marijan we get the last cup of sugar with some tea. He wants to know everything about my country, Holland. I ask him back: what do you think is more dangerous? Living in a country that is below sea level, or on top of an active volcano? He pauses to think. “Sama” (“same”). He chuckles. “As long as God gives you life, he gives you security. But we are also afraid. Wherever you live, you always run risks. Also in the Netherlands, right?”.

How did he become gatekeeper actually? “Ah, the Sultan has appointed me, because there is no natural successor. It has always been an ordinary farmer like me. I get a modest salary for the old days. It's not about money, it's about the mountain. I am the official gatekeeper, but I really do not wear an uniform or something. And who will be my successor, I don’t know. My son maybe, if he feels like it, but it could be anyone, even a girl could do the job”.

Lethal party

There is a seismologic institute on the mountain, but you seem only to listen to the ghosts. Why don’t you believe in technology? “I always say; if a smart man asks, he always wants to know more. Only a fool is happy with what he knows already. We believe that if the volcanic spits out gas, ash, smoke and stones, it is an expression of the kraton in the Merapi. They are celebrating and throw out the dirt to clean their palace, as we do with new years”.

But that party can be lethal. “Yes, if the Merapi explodes, it is because the mountain does not want the people no longer. It is a sign that people have forgotten who they really are”.

Are you saying it is the fault of the people if the Merapi erupts? “You must understand that we all lost family and friends to the gas clouds and lava. We accept that is our fate. We believe that if a village is burned by lava, that's because the people are not religious. I believe and enjoy every day all the beauty that life offers. That’s life”.

Mbah Marijan died on October 25th 2010, when the Merapi lava burnt his house (news link).

_____________________________________________________________________________

Anak Wayang helps

With Anak Wayang Netherlands, we transfer a donation this week for Anak Wayang Indonesia, a local child rights NGO in Yogyakarta, that is organizing emergency aid for the victims of the volcano. Please email info@anakwayang.nl for more information or a donation.